Révisions

Factorizing trees

We have seen that a large coverage TAG may have many trees (several thousand trees, and easily more), but with the elementary tree sharing many fragment. For efficiency reason, it is interesting to reduce the number of trees by factorizing them, sharing the common parts and using regexp-like regular operators to handle the other parts. These regular operators, like the disjunction, does not change the expressive power of the TAGs because they can always by unfactorizing to get a finite set of equivalent non-factorized trees.

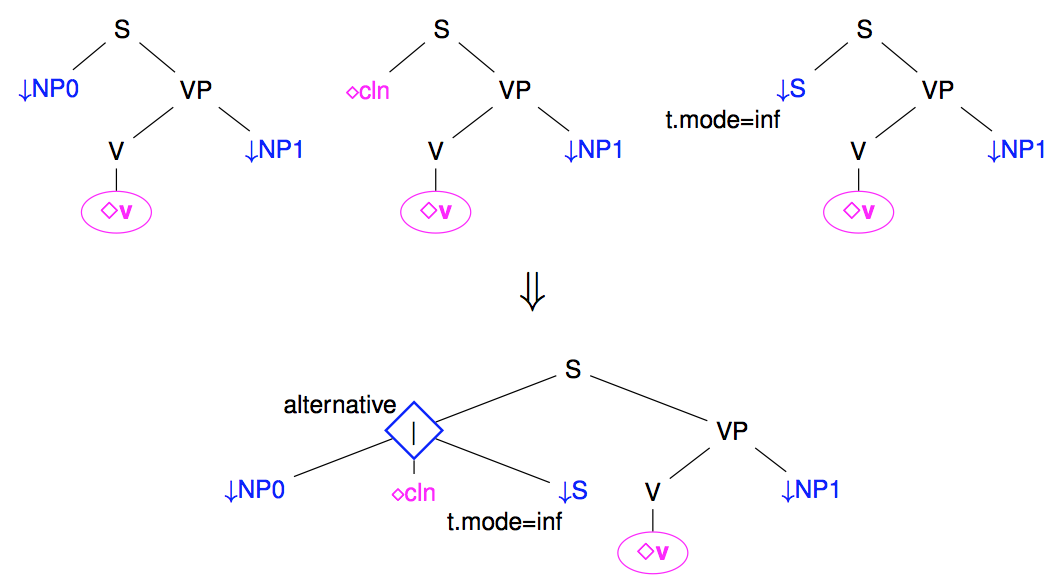

Disjunctions

When several subtrees may branch under a same node, we may use a disjunction to group the set of alternatives subtrees. For instance, the following figure shows how several possible realizations for French subjects (as Nominal Phrase, clitics, or infinitive sentences) may be grouped under a disjunction node (noted as a diamond node).

Note: Disjunction nodes are associated with type: alternative in meta-grammar descriptions

Guards

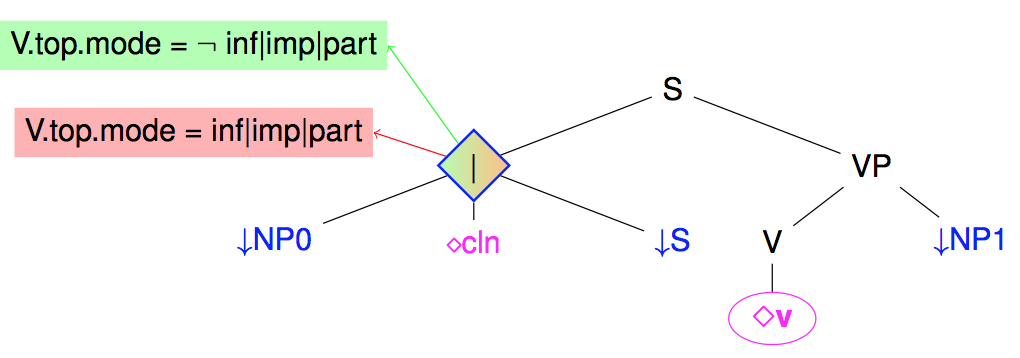

Disjunction may be used to state that a subtree rooted at some node N is present or not. However, the presence or absence of a subtree is often controlled by some conditions. Such situations may be captured by guards on nodes, with the conditions being expressing as boolean formula over equations between feature paths (and feature values).

The following figure illustrates the use of a guard over the previous suject disjunction node to state that a subject is present in French when the verb mood is not infinitive, participial, or imperative, and absent otherwise.

Note: at the level of meta-grammars, the guards are essentially introduced by the => operator on nodes.

For a positive guard on a node N (ie the conditions for its presence) :

For a negative guard on N (ie conditions for its absence), the node must be prefixed by ~

A positive or negative on a node N implicitly implies a true guard for the opposite side, to be then refined by explicit guards. All occurrences of guards on N are aggregated using an AND operators.

It may also be noted that even if a node N is always present, it may be interesting to set up a positive guard on n to represent different alternatives. A special notation may be used for that implicitly set a fail condition on absence (i.e. the node can't be absent!)

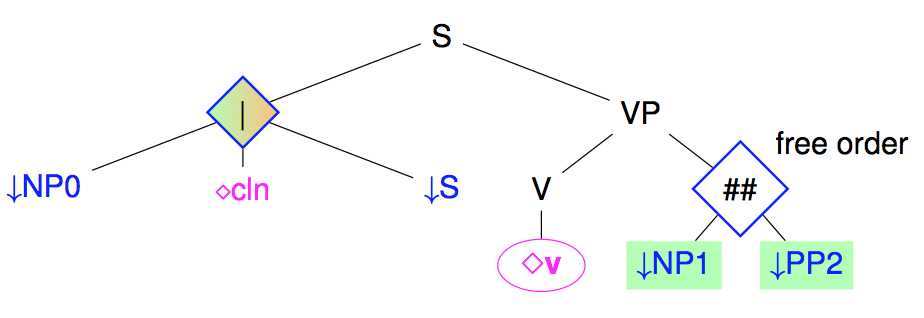

Free ordering (shuffling)

Some language are relatively free in terms of ordering of the constituents. This is not really the case for French, but for the placement of post-verbal arguments. Rather than multiplying the number of trees for each possible node ordering, it is possible to use shuffling nodes that allows free ordering between its children.

Note: at the level of meta-grammar, there is no need to explicitly introduce shuffle nodes. If the ordering between brother nodes is underspecified given the constraints of the meta-grammar, a shuffle node will be introduced in the generated tree.

Note: The shuffle operator is actually more complex than just presented. It works between sequences of nodes rather than just between nodes, interleaving freely the nodes of different sequences but preserving order in each sequence. For instance, shuffling the two sequences (A,B) with (N) will produce all 3 sequences

- (A,B,N)

- (A,N,B)

- (N,A,B)

If we examine our example tree, we can try to count how many trees it represents when unfactoring it (assuming guards on subjects and optionality on NP1 and PP2). We actually get (1nosubj+3subj)∗(1noargs+21arg+22args)=20trees.

Repetition

- Version imprimable

- Connectez-vous ou inscrivez-vous pour publier un commentaire